It’s Serial Tuesday! That’s not a thing, but it could be. It is today! Anyway, here’s the second installment of the creeping science fiction novella that won second place, second quarter, in the Writers of the Future Award last year!

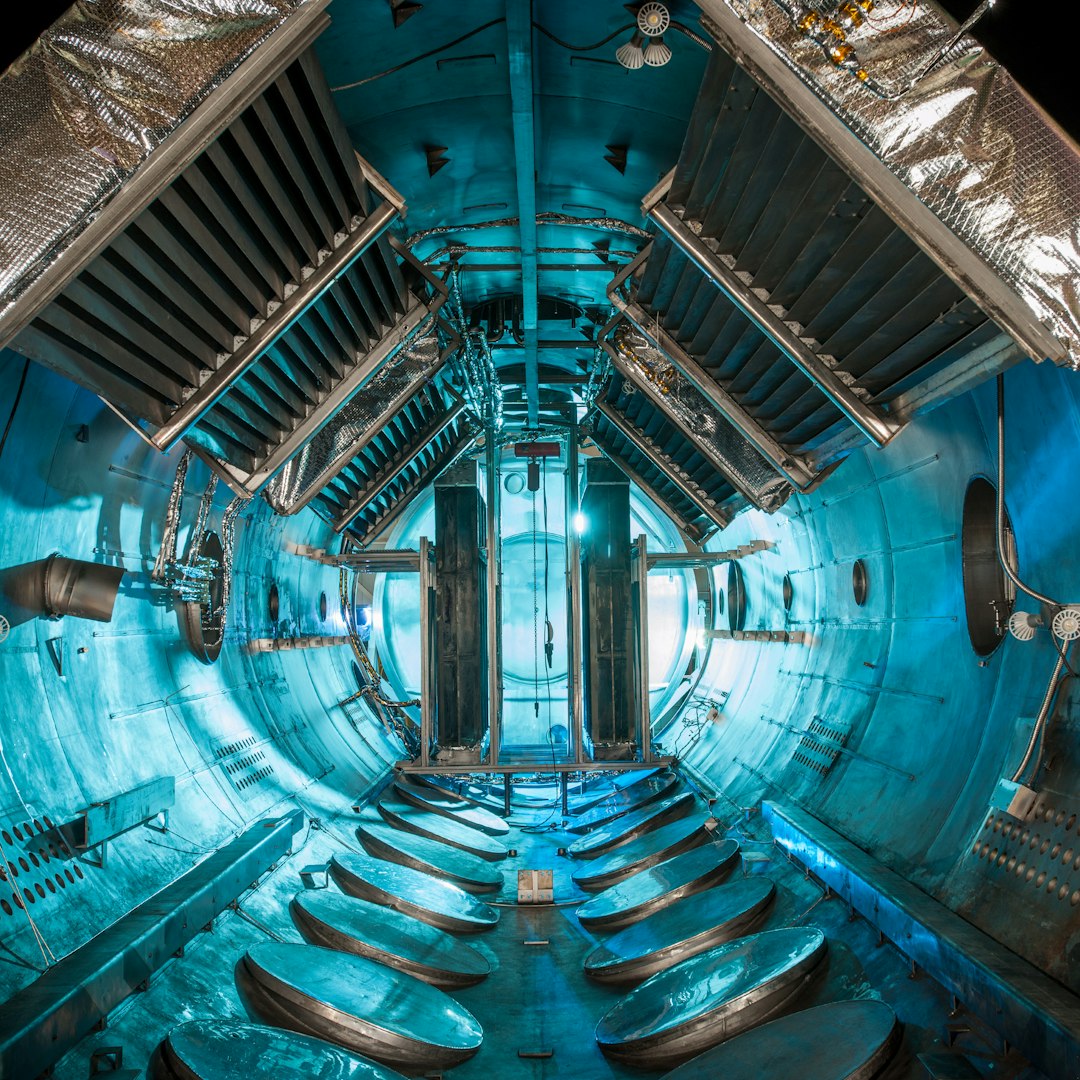

Is anyone else getting “Event Horizon” vibes? Just me?

Read part 1 here

If this entire post doesn’t show in your email, try the webpage or the app

The Withering Sky

part 2 (middle)

by Arthur H. Manners

“It’s obviously a lab. Something funded off the books, a place to run all the research too nasty to see the light of day. It got out of hand, and now they’re cleaning up,” Vezzin said, sounding bored. I wanted to throw him into the corridor, see how bored he was then.

Speculation had become a central pastime. We had grown bored of guessing when the research team might arrive—it was obvious that they would show up when they felt like it. But it was open season when it came to the nature of the object.

Kitamura thought it was military, a psychological weapons outfit hidden beyond regulated space. M’Bele changed his guess every few minutes, ranging from mundane to wacky.

Rogers refused to offer her own thoughts.

I was the only one who suggested it might have come from farther away. It wasn’t impossible; the probes dispatched to Alpha Centauri, Procyon and Epsilon Eridani had succeeded, after all. Maybe somebody had managed a round-trip mission.

“They hollowed out an entire asteroid for a black-site lab? We might have explored a few kilometres’ worth, but you could fit a small city in here,” M’Bele said, considering his hand.

The others were playing cards. I itched to join them, but I held off. I was no stranger to dropping a couple grand on the table and talking big, then waking up in an alley with empty pockets. But I’d been clean for weeks now. No point putting up with this freak show only to emerge ready to gamble away my pot of gold.

“Okay, big shot. What do you think it is?” Vezzin spat.

M’Bele upped the ante. “I’m certain it’s an alien spaceship.”

Everyone scoffed.

“If it was alien, why would it have Earth-standard gravity and atmosphere? Everything is custom made for humans,” Rogers said. She seemed more intrigued that sceptical. She called.

“Though, if it was made by humans, it would be as cut-rate and grimy as every other station in the system,” I said. My fingers twitched as I glimpsed the straight flush in Rogers's hand.

“Not if you know the right people. I’ve been on some stations Mars-side that look like they were designed by Dali with Solomon’s gold,” Kitamura said. She folded.

“Oh, yeah? Did they have the nightmare murals there, too?” I said, and regretted it. The fun went out of the conversation as soon as we thought about the mural.

Rogers threw down, and everyone groaned. She was on a streak.

It went on like that for a while. By day, we wandered and tried not to think about what we found. By night, we speculated in the imagined safety of one another’s company.

No doubt Bouvard knew more than we did. Maybe they even had a reason for not towing everything back to Neptune and cracking this freaky little egg open.

But we were clueless. Even the shape of the object defied understanding. We had seen from the outside that it was cylindrical, and kilometres tall, but we never found any staircases leading to other decks.

Vezzin and M’Bele wanted to use the shuttle radio to demand more information—the one thing they could agree on.

Kitamura, Rogers and I didn’t want to jeopardise the brief.

We danced precariously around the growing divide between us. Kitamura knew better than to overextend her position, announcing sorties into the corridor just before Vezzin and M’Bele boiled over. I took these trips as gifts, a taste of the freedom I craved, even when we found things that defied the laws of physics. But it was obvious that our situation couldn’t last.

“What are we babysitting, the object or them?” I said.

Kitamura didn’t laugh.

Vezzin started playing music at night to mask the silence. He claimed that it worked, but I could still hear everybody breathing. As soon as morning came, the bickering would start again.

###

Rogers started experiments. Most of it was too technical for us, but we did help her study the optical effects of the corridor. I remembered enough college physics to get the gist of what she was doing, but mostly I did as I was told.

“Has it occurred to you that Rogers is the only person who should be here?” I said.

Kitamura grunted, her arms and legs splayed out like the Vitruvian man. Apparently it helped Rogers gauge the aberration close to the vanishing horizon. Or it could have just amused her. “What makes you say that?”

“The rest of us aren’t physicists or engineers or whatever she is.”

“Vezzin’s an engineer.”

“Yeah, and a big help he is.”

“Mmm. You’re assuming they wanted us to study the thing at all. We’re supposed to be babysitters.”

“No way would they send us here just to sit on this place. What’s taking the research team so long? There’s enough here to occupy every researcher between here and Mars for years.”

She didn’t have an answer for that. I watched the familiar discomfort play out on her face. Before I could press her, she changed tack. “So, are you going to tell me why you need this money so bad? Any sane person would be on Vezzin and M’Bele’s side.”

I pretended to tune my radio. I had managed to avoid the topic so far, and wanted to keep it that way.

Kitamura shrugged. “I want to run my own outfit,” she said, as though I’d asked. “Seed money like this is hard to come by. Plus, whoever our employers are, they’ll be good people to have on my side.

“As for the rest of you. Well, Vezzin’s a coward, so whatever. M’Bele is too sensible to be as stupid as the rest of us. Pretty sure they just straight up lied to get him here. Rogers is a head case who would walk into fire to measure the temperature of flames. But you, I’m not sure. I figure you’re running. What I can’t figure is whether you’re running to something, or away from something.”

I looked down the corridor towards Rogers, who shimmered at the edge of the vanishing point. “Me neither,” I said.

What did I tell her? That I had everything given to me but hated every second of comfort. That I wandered until there was nowhere to go but off-planet. That I gambled and drank my way to the edge of occupied space, and spent ten years wandering the ice, half frozen to death, just so I didn’t have to think.

I almost broke the silence, but Kitamura spoke first, oblivious.

“Well, I hope you figure it out, because I can’t pretend I know what I’m doing forever. Who knows why those bastards put us here. Stay or go, we’re going to need to trust each other to get through this.”

I nodded, but I was disappointed and frightened. I had been hoping that secretly she knew at least a little more than the rest of us.

Rogers's ambition didn’t stop at the corridor. She wanted to study the mural. She had all kinds of ideas—ideas I couldn’t begin to understand.

But Kitamura made sure nobody went near that room alone. Visits were limited to a few minutes, always in pairs, with one person facing the corridor at all times. I guessed she was afraid one of us might be hypnotised or something. I didn’t blame her.

We stopped splitting up when we explored. We dragged M’Bele with us when we could, though he and Vezzin almost seemed distressed to be separated. In some twisted way, their fighting had become a comfort.

I was braced for a repeat of the mural, but most of the other rooms were empty or just quietly inexplicable. One room had a bench in it—not an acceleration harness or a storage rack, but a wooden park bench.

“At least it’s familiar,” I said.

“Somehow I’m not relieved,” Kitamura said.

###

“Where are you?” I said.

I stood in the sixth room rightward of the antechamber, which housed the only window we’d found. It showed nothing, just empty space dotted with stars, but I kept coming back.

I told the others I was watching for the research crew, but I didn’t expect them any time soon. Two weeks had passed and we’d heard nothing.

We had edged towards panic at one point, but relaxed when we took inventory and found the pallet had supplies for months. They must have anticipated delays.

Really, I had returned to the window because sun-bathed Earth was somewhere in the darkness. Out on the frontier, home was nothing but a fantasy. As unreal as the phantoms and streaks of light people saw as their eyeballs deformed in microgravity.

There was nothing but time on the object. Time and silence. I took any opportunity I could to wander and explore, but my body needed to rest eventually. When I stopped, my mind couldn’t avoid itself.

“Where are you?” I repeated.

I had said it more often the last few years, whenever I was forced to stop, and realised that I barely recognised myself.

Was all this worth it? I hadn’t heard from my parents since the last round of rehab on Bouvard. They had to remortgage the house to pay for it. They knew it wouldn’t stick, so when I relapsed, they didn’t call.

I didn’t dare hope that we could narrow the chasm between us. Some things couldn’t be unsaid. But maybe if I could just see them again, I’d have something to fight for.

All the same, in the unforgiving light of the corridor, it all seemed pathetic, ridiculous.

What was I trying to go back to?

I probed my head. I knew that pressure must be there; every night it tore through my forehead like snarled hair yanked from a rusty pipe.

I knew I hadn’t been sleeping for more than an hour a night. I should have been in pieces by now, delirious and barely able to stand. But I was starting to feel more alert than ever, and when I breathed, I could almost feel the walls swell around me—

Rogers burst into the room. “Vezzin’s dead.”

I followed, numb. The antechamber amplified M’Bele and Kitamura’s silence. For a while we became a melodramatic fresco—them flanking Vezzin’s body, me and Rogers staring across it.

M’Bele broke the spell by taking a step back. Only then did it become clear that we were all staring at him. I hadn’t even been aware of it.

“No, no. This has nothing to do with me,” he said.

I punctured the short silence. “You’ve been at one another’s throats since we got here.”

“No, I was with Kitamura the whole time. Right?”

Kitamura nodded slowly. “That’s right.”

“Don’t look at me like that! How could I have done this? Look at him!”

I had thought Vezzin’s limbs were askew, but now I noticed one arm and both legs were bent the wrong way at the elbow and knees. His neck looked strange and had turned purple.

M’Bele was a big man, but to inflict that kind of damage he’d have needed the strength to break bricks with his hands. There was no sign of a weapon, or a struggle.

“Did you lose sight of him, even for a second?” I said.

“No,” Kitamura said. “We were pretty far down the corridor.” Her jaw clenched and with visible effort turned her back on M’Bele. “Couldn’t have been him. Either there’s somebody else here, or . . .” She cleared her throat. “We might be in trouble.”

###

Kitamura and I fussed over what to do with Vezzin, before Rogers produced a body bag.

“From the pallet,” she said in response to our shock.

“Why didn’t you tell us there were body bags in the pallet?” I said.

“They were right there. I thought you knew.”

I wondered what else I’d missed.

Kitamura went to the shuttle to radio for help. “Enough delays,” she said.

“Wait!” I yelled in unison with Rogers.

“We can’t break radio silence. There are so many questions. They’ll take over, kick us out,” Rogers said.

“That’s the point,” Kitamura said. Her gaze switched to me.

A dozen conflicting thoughts clogged my throat. I could only stare back at her.

Whatever Kitamura saw in my eyes, she didn’t like it. “A man is dead,” she said coldly, and went into the shuttle.

I stayed with Rogers to deal with Vezzin. We had to straighten his limbs to get him into the bag. I grimaced at the prospect, but Rogers whisked me aside and arranged the body, businesslike. I heard something crunch in Vezzin’s leg.

Kitamura emerged from the shuttle. “I can’t raise anyone.”

I stiffened. “What?”

“I thought they just weren’t answering, but I’m not even getting static. I think the shuttle radio is dead.”

“That’s the only thing we have powerful enough to reach Bouvard.”

M’Bele let out a quiet moan and began to rock back and forth.

I touched my forehead. The pain had lurched up to my conscious awareness.

Kitamura looked stricken as though grasping for control.

Rogers looked between us, the same intrigued expression on her face as when she studied the corridor.

“What’s the matter with you. Doesn’t anything bother you?” I said.

She shrugged.

“Can you fix it?” Kitamura said.

“Maybe. Vezzin was the mechanic.”

“Try.”

Rogers vanished into the shuttle. After an hour, she reported that nothing seemed obviously broken. I wasn’t sure I believed her.

“Fine. They’ll arrive soon, anyway,” Kitamura said. She sounded far from certain.

“Wake up!” M’Bele yelled. “It’s obvious—we’re some kind of sick offering.”

“Don’t be ridiculous. You talk as though this place is alive,” I said.

“I don’t know what it is, but I’m certain it’s not totally dead, either.” He looked around. “Come on, you’re all thinking it.”

“The only reason we’re here is to get paid and get out of here. Now stop it, you’re scaring everybody,” Kitamura said.

“Somebody is dead! Something is in here with us.”

“There’s nothing in here except our imaginations, and a few buggy experiments. We’ll contact Bouvard, get double hazard pay, feel sad for a minute, then move on. Don’t tell me you’ve never taken a dangerous job before.”

M’Bele fumed, but I could see the fight had drained out of him.

It was getting late. None of us wanted to stay in the antechamber, but there was nowhere else to go. I considered suggesting we pile into the shuttle and seal the doors. Then I thought of being cooped up with Rogers bouncing off the walls, and M’Bele rocking like an earthquake survivor.

We opted for our tents, though we pushed them against the shuttle doors, in case we had to retreat.

“How can there be anyone else here? We’d have seen them by now,” I said.

“Who knows how much farther the corridor goes,” Kitamura said.

“Far. We haven’t scratched the surface,” Rogers said sleepily.

I tried to ignore that. “You’ll fix the radio, right?”

But she was asleep or at least pretending to be.

We set a watch. I didn’t expect to sleep, so I stayed up with Kitamura.

M’Bele sounded like somebody in the grips of fever. He tossed and muttered broken sentences. Several times we saw his silhouette bolt upright.

“Do you think we’ve all been like that every night?” I said.

“I’m trying not to think about it,” Kitamura said.

“What if we can’t call for help?”

“Like I said, the research team will be here any minute. This thing has got to be valuable to them to go through all this smoke and mirrors bullshit.”

“What if they decide it’s too much risk. What’s to stop them from leaving this thing out here and saying they lost us in an accident?”

Kitamura scratched her nose. “You’ve been watching too many movies.”

###

I woke to a throbbing headache. Kitamura and Rogers were already up, having taken the last watch.

“Let’s go get the bastard,” I announced.

“What?” Kitamura said.

“Vezzin wasn’t killed by some rogue experiment. There’s somebody in here who wants us gone.”

“You’re serious,” M’Bele said. He glanced at Kitamura. “It would explain why you’re here.”

“Whatever. No more than one person could hide in here, no matter how big this place is. There are four of us left. Let’s go get them.”

Kitamura opened her breakfast rations. “If there is somebody else here, and they killed Vezzin, they’re armed with something that breaks bones like twigs. Four unarmed people against one person with . . . what, a sledgehammer? Not good odds.”

I paused to think about it, but Rogers was giving me that same strange look, as though I were a bird in cage somehow twittering human speech. “If I don’t get out of this room, I’m going to explode.”

“What about fixing the radio?”

“Even if Rogers can fix it, I’m pretty sure she’s not going to do it in a hurry.” I turned to Rogers. “No offence, but you’re all kinds of crazy.”

She paused a moment, then shrugged.

Kitamura put her head in her hands. “Fine. Suicidal manhunt it is.”

M’Bele took some convincing, but one glance at the body bag in the corner brought him around. We headed out leftward, keeping together, holding a few wrenches for protection. By the afternoon we’d reached the fifteenth room, the furthest we’d gone. It was an office—a run-of-the-mill Earth-side office—complete with budget upholstery. There was even a water cooler. But there was also a pungent smell, like farm animals.

“Looks like we found the accounting deck,” I said.

Something bumped the underside of the desk beside me, and I froze. Before I could run, M’Bele hauled a pile of rags from under the desk, writhing and screeching in his grip.

M’Bele skittered back. “What the hell.”

I could now see that the pitiful thing was a small man in his forties, cowering on the floor.

Rogers crouched beside him. I had the impression of a butterfly collector observing a specimen mounted upon a needle. “Who are you?”

He answered with another whimper. He stank, his clothes caked in dried excretions. Kitamura recoiled from another desk, where the man had been relieving himself.

Rogers crooned to the man despite the stench, and by degrees he calmed.

M’Bele and Kitamura wanted to tie him up, convinced he had killed Vezzin. I didn’t think he looked strong enough to stand; breaking every bone in a person’s body seemed a stretch.

Nearby we found supplies, scraps of clothing that had been fashioned into a backpack, a photograph of a young man toasting the camera with a bottle of beer.

After a few minutes the man answered M’Bele’s questions.

“Transport crew.” His voice was thin and broken. “Bouvard sent us. A . . . a supply drop.”

“The pallet? Back in the antechamber?” Kitamura said.

“Routine drop. Supposed to be back on station for dinner.” He turned haunted eyes on us. “They promised.”

“What happened?”

The man withdrew, curling up on the floor, and Rogers had to coax him back out.

“We unloaded the gear, spent the night. Then the shuttle was gone. The others went away and it was just me.”

“What happened to the shuttle?”

“How many others?” said M’Bele.

“What happened to them?” said Kitamura.

“Guys,” I warned.

But it was too late. The man shook his head in violent jerks and began crawling away. “Noooooo . . .” he moaned.

“Let’s get him back to camp. This is ridiculous, there’s no way he’s going to make sense in this condition,” I said.

“Seconded,” Rogers said.

Kitamura and M’Bele made a show of reluctance, but there wasn’t much else we could do. He obviously hadn’t killed Vezzin.

We got him back without trouble. We forced him into the shower and fed him, but he fell asleep before we could get him talking again.

“Think he’ll run?” I said.

“We could put him in the shuttle,” Rogers said.

“Not a chance are we putting him in there. He might sabotage it,” Kitamura said.

So we watched him kicking and moaning like a dog. We took shifts again, one to watch the door and one to watch the stranger. And in the middle of the night, with the pressure creeping through my forehead, I cringed at the thought that another crew had been here and only he remained.

###

Kitamura woke screaming in the night. Cool, calm Kitamura. She flailed and wept fat tears as we pulled her from her tent.

The stranger watched, owlish.

Once Kitamura was settled, I touched my temple unconsciously, searching for that creeping pressure. It was getting to us all. If we hadn’t set a watch, might some of us have become like the stranger’s crew—just walked off into the dark somewhere?

The next day, our guest started talking in earnest. The only problem was that it was all nonsense words, interspersed with screeches and hisses. He would startle suddenly, as though an explosion had gone off, and we had to restrain him. Sometimes I thought he might be saying something coherent, but it was always too quiet to make out.

He wouldn’t tell us his name. For whatever reason, that question frightened him most.

We couldn’t wait around forever. We dragged him back into the corridor, visiting the fourteenth, fifteenth and sixteenth rooms rightward of the antechamber. They were boring, housing more storage containers, but something didn’t feel right.

I realised late in the afternoon what was bothering me: the distances just didn’t tally. We should have reached the far-side hull by now. We had gone beyond the external physical dimension of the object.

Rogers was thrilled.

Kitamura suggested the hallways were indeed bent imperceptibly, and that we would eventually find our way back to the antechamber. To check, we left a sonic beacon in the seventeenth room and hiked all the way to the fifteenth chamber on the leftward side. It was late by then, later than we’d ever stayed out, but none of us wanted to stop.

We had set the beacon to emit a one-hundred-twenty decibel ping on a one-minute cycle. Loud as a jet engine. We all stood straining to listen.

And heard nothing.

“Guess it’s not curved,” I said.

Kitamura didn’t reply. I guessed she was remembering our first trip, when we had heard one another through the walls.

We made it to the antechamber exhausted. We managed only four hours of sleep before the stranger leapt wailing across the chamber, knocking Rogers flying. I tried to stop him and received a punch to the neck. He almost made it to the door before M’Bele tackled him.

Snarling, M’Bele tied him up. The man didn’t struggle, but M’Bele threw him around like a doll and kicked him in the ribs. It took all of us to drag M’Bele away.

“He killed Vezzin. Why else would he run?” M’Bele roared. He didn’t seem at all like the calm, measured man who had stepped aboard.

“Go set watch. I don’t want to see you again until we move out in the morning,” Kitamura said.

For a moment I thought he’d attack her as well, but he crumpled and trudged away.

None of us bothered trying to sleep again. A dangerous lunatic was one thing, but I was more worried about waking up in a panic and hurting someone.

###

Rogers toyed with the radio all night, but claimed to have made no progress. I was beginning to doubt that she was trying at all.

“They’re not coming for us, are they?” M’Bele said, slumping against a crate.

“We don’t know that,” I said, but it was only a reflex. I felt it in my bones—if we were getting out of here, it would be on our own steam.

Kitamura led us into the corridor before we could eat breakfast. “This thing can’t go on forever,” she growled.

M’Bele pushed and manhandled the stranger. The look in his eye dared us to say something. Kitamura and I did our best to smooth things over, the danger we sensed communicated in stolen glances.

Before long, I was flagging. Stress had bullied my body into a constant tremble, and my mind felt like stretched taffy.

Yet, a part of me hoped that the corridor would just keep going. I was beginning to savour the silence, the simple unending process of putting one foot in front of another, watching the unknown appear from the darkness.

I worried what would happen when it ran out—no matter how hard I ran from myself, the road always ran out.

Then we reached the twentieth chamber leftward of the antechamber, and my petty troubles didn’t matter anymore, because the twentieth chamber was filled with bodies.

The forms were charred, melted and misshapen things, the features lost. But there was no mistaking the arms, legs, heads and torsos. A few were clustered close to the door, their burned hands reaching for the corridor. Two of them sat against the far wall, embracing.

“Still they see the too bright faces of the many,” the stranger said.

“Do you know what happened here?” I said.

But he was gone again, into his own world.

M’Bele backed out from the room, breathing fast.

I held up my hands. “Cool it. Whatever happened, it happened a while ago.”

“You don’t know that! You don’t know anything. None of us do. We’re searching this place like we’ll find something that’ll change anything. What in here is going to get us back to Bouvard?”

“Just breathe,” Kitamura said.

“No. I’m done. We all know what happened to this guy’s friends. Either he killed all of them and he’ll go for us next, or something a lot worse than him is in here. You can get yourselves killed if you want, but I’m getting out of here.”

He ran.

“The shuttle!” Kitamura said.

We tried to follow, but we were hobbled by the stranger’s shuffling pace. We ended up half-carrying, half-dragging him. By the time we made it back to the antechamber, I was certain the shuttle would be gone.

It was still there, but Rogers reported that the shuttle radio module and most of our tools were missing. M’Bele had taken his tent as well, and enough rations for a week.

Kitamura wanted to go after him, but I stopped her. There were only the three of us now. Between us we could take M’Bele if things went bad, but one of us was bound to get hurt.

We spent a wary evening with our attention split between the stranger and the door. The air seemed denser, the heaviness of anticipation.

M’Bele didn’t materialise. Still we sat, waiting, until sometime late the next day.

“We need to go,” Kitamura said. “Overwrite the shuttle somehow. Send help for M’Bele once we get to Bouvard.”

A part of me had been screaming the same thing. Nothing was worth this.

But it made me dizzy to think about going this far only to give up and go home with nothing.

“You go. I’m staying,” Rogers said.

Kitamura rolled her eyes and looked to me for backup.

She was right: we had to go. This was the moment to step up, do the right thing. But I hesitated a beat too long, and Kitamura’s expression sobered, then hardened. She wasn’t going to be the sole survivor, the captain who abandoned ship and let her crew drown in shadows.

I felt sorry for her. But the truth anchored me to this nightmare—I couldn’t leave, not yet.

We went through the motions of eating and resting, but the atmosphere between us had changed. If there had been an alliance, it was now broken.

I was startled but not surprised when I woke the next morning and found Kitamura gone. Rogers, who was supposed to be on watch, only shrugged when I asked what happened.

“She went to get M’Bele,” she said.

I didn’t bother asking why they didn’t wake me. Rogers was working on a pile of wires and micro-monitors. I left her to it, and spent the day with the stranger instead.

Rogers announced she had to go run some experiments on the mural. We fought for a while, but it became clear that it didn’t matter what I said. I was beginning to hate her, but I knew that if I didn’t go with her then I’d never see her again. And that would leave me alone. So we were both going.

Luckily, the stranger was content to be led like a dog on a leash. I spoke to him as we headed out, about what I’d say to my parents, about my luckless time on Triton, my addictions and frustrations. I sensed he was listening, even while he twitched and stared about.

I called out for Kitamura, and tried to raise her on my radio. Several times I thought of doing the same for M’Bele, but thought better of it.

We reached the mural without incident. The stranger let out a soft gasp as we entered the room. I half expected him to freak out, but instead he sank to the floor and sat cross-legged, mesmerised.

I kept my gaze on Rogers, asking questions about the experiment, keeping my mind busy. It worked for a while. The mural didn’t look like much, maybe a few dark streaks on the far wall. I helped Rogers set up.

Then the heart palpitations started. Invisible hands gripped my head, trying to force me to look at the wall. I focused on breathing, on not looking up, but the flutter in my chest grew, sending me gasping. “Rogers!”

“Incredible,” Rogers said.

I glanced at the wall, and a vice closed around my chest. “Rogers, we have to get out of here.”

“Do you see it?” Rogers muttered.

“There’s nothing there. Listen—we’re leaving.”

I tried to reach for her but my arms had become lead weights. There was no way to not look. It was as though my eyelids had been taped open.

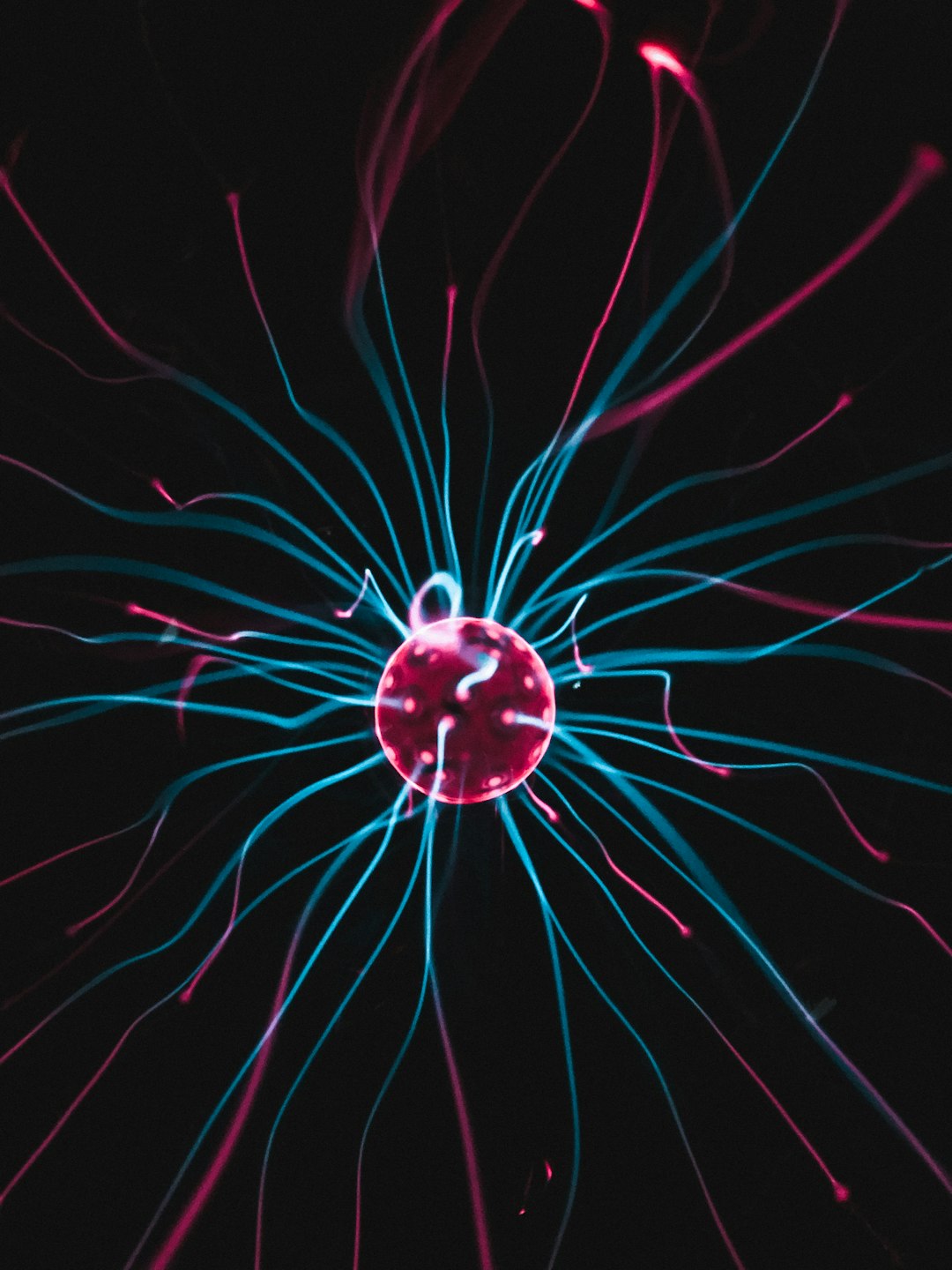

My body thrummed like a struck gong. Those invisible fingers slithered under my scalp, digging into the soft parts of my mind. Flashes of anger, terror, lust, hunger. I avoided wetting myself by a hair.

The mural came alive, different to last time: bright colours on top and a dark form below. A procession of figures gathered, their features only hinted at by bright swirls, like a negative of an expressionist painting. The whole thing shifted and danced, kaleidoscopic. I was looking right at it, but some part of me was also convinced I was looking at a blank wall.

“Rogers.”

The dark thing rose to penetrate the standing figures. They raised their arms, mouths opening—whether to pray or scream, I couldn’t tell. Then they began to buckle, and somehow I knew they were melting.

Rogers smiled. “This answers so many questions. So elegant.”

Whatever she was seeing, I doubted it was what I saw.

I turned to run, and saw the stranger with his arms raised; he began to sing a high, continuous note—cut short when I collided with him and tackled him into the hallway. I landed on top of him, heard something crack. He shrieked.

“Rogers, come on!”

She didn’t move. I dragged the stranger away by the collar, bouncing him off the walls. Either he was a lot lighter than he looked or I had summoned the strength of ten people.

I made it most of the way back to camp before I slowed down. The silence hit hard then, punctuated only by the stranger’s whimpers. At last, the grip on my heart loosened, the fingers in my mind retreating just enough to let me think.

I had left Rogers back there. I just left her.

But I didn’t bother trying to go back, knew that I wouldn’t be able to turn my feet. I needed a plan first.

The stranger was cradling his shoulder. He seemed to be fading by the moment, a bundle of bones in a paper bag.

This is all I had left for company?

I soon gave up trying to raise anyone on the radio. I wanted to crawl into my tent and sleep for days, to escape everything I could not understand.

We were fifty metres from the antechamber door when Kitamura stepped into the hallway. She was laden with supplies, looking the other way. Her jumpsuit had a big tear down one side.

I called out to her, breaking into a run despite the stranger’s dead weight.

She started walking the other way, rightward of the antechamber. She disappeared within seconds, a mere ten metres from the chamber—a far shorter vanishing horizon than I had seen before.

I went past the chamber door, five metres, then ten, then twenty. She didn’t come back into sight. I stopped when the antechamber vanished behind me, not daring to go farther.

I called her name for the better part of an hour. In that time, nothing stirred but the ragged flutter in my chest, and the whimpering stranger at my heel.

There was no choice but to sleep. I tied the stranger’s wrists and ankles and fenced him in with supply crates. He didn’t protest, but curled up like a dog and fell into a muttering sleep.

I took a long length of pipe from the shower, and pulled my sleeping bag into the shuttle. I closed the airlock and wedged the pipe through the locking wheel.

I managed not to scream only by imagining the peace of mind I would feel when I got home, when my parents took me in and blew away the spiders in my brain. I would get through this—all I had to do was hold onto that future.

I must have fallen asleep because the next thing I did was I jerk awake. The stranger was making a low keening noise.

The locking wheel wrenched an inch clockwise. The pipe holding it in place groaned, but held.

“Rogers?” I whispered.

No answer.

After a while the sound died away. The pipe had bent. I wasn’t sure even M’Bele would have been strong enough to do that. I tried not to think about Vezzin’s twisted body, and went back to sleep.

—to be continued—

Read part 3 (conclusion) here

Meet the author:

Arthur H. Manners is a British writer with a background in physics and data science. He recently encountered the underside of life when he ended up stranded for hours in Helsinki Airport, alone—except for a snack shop clerk who looked as bewildered to be there as he was. His short fiction is published/forthcoming in Dreamforge Anvil, Drabblecast and Writers of the Future Vol. 39. In 2023, "The Withering Sky" received the Writers of the Future award. Arthur sometimes fails at social media on Twitter (@a_h_manners) and Instagram (docmanners). Find his newsletter over at arthurmanners.com.

Your next read:

Promise the Girl

The following story continues a long tradition of rockets, space exploration, and AI control. Such stories come with expectations. We call those expectations “tropes.” And while this one hits many of the correct notes, or tropes, the ending will differ from many that came before.

A Scuffle for a Wrinkle, pt 1

Vonnel and his crack team plan to steal a device that bends space-time, but someone else wants it too. That is the tagline for one of my earliest published stories. Does it entice you? If so, it worked! If not, are you okay? Have you hydrated properly and been getting enough sleep? But I digress. The story still shows up on Amazon, although its small pub…

Relay

It’s April, and it’s snowing. At least here in Colorado. But enough about the weather. In the outside world, inflation is soaring, AI is taking over, and a starship prototype exploded, possibly on purpose? So let’s take another look at the underside.